Wealth and Appreciation

/From the FF alumni newsletter:

Hi Financial Freedom gang! Hope this fall is off to a good start! Some pieces of news from the PUGS FF world:

1. Did you hear that I'm stepping down from PUGS? I'm doing so to teach more and feel more free to travel more next year. I'm thinking of doing a 3 month temporary relocation to Victoria BC to see if I like it. I want PUGS to grow and be of great service to Portland, unrestrained by me.

2. I've been surveying alumni about how the impact of FF1 on their finances. I've been hearing that people are saving $100-$800 a month(!) after taking the course. That's amazing. I'm proud of the course and of all the change everyone is reporting.

3. The one crazy outlier: someone told me yesterday that she and her husband have saved $64,000 in the 18 months since they took FF1. Holy crap. It was a combination of improved defense and much much more offense. She attributed it to a major attitude change since FF1. THAT's taking control of your finances.

4. Last week, I gave a talk at the Whidbey Institute conference Money Meaning and Power. Vicki Robin, the author of Your Money or Your Life (the book that started the FIRE movement in the 1990s) gave a talk about the policies that we need to create #financialfreedomforall. The policies included universal health care, free education, and universal basic income. Financial freedom shouldn't be exclusive and for the privileged. Super interesting. My talk was called, "Capitalism isn't the problem, you are." I was told to be controversial. haha. You basically know what I talked about: consumerism, the Story of Stuff, lagom, the carbon footprints of liberals being higher than conservatives etc. If I get the video, I'll send it to you.

5. What I've been thinking about: frictionless spending. Making the space and thought between a consumer's desire and their purchasing is the next frontier of market capitalism. Scary stuff.

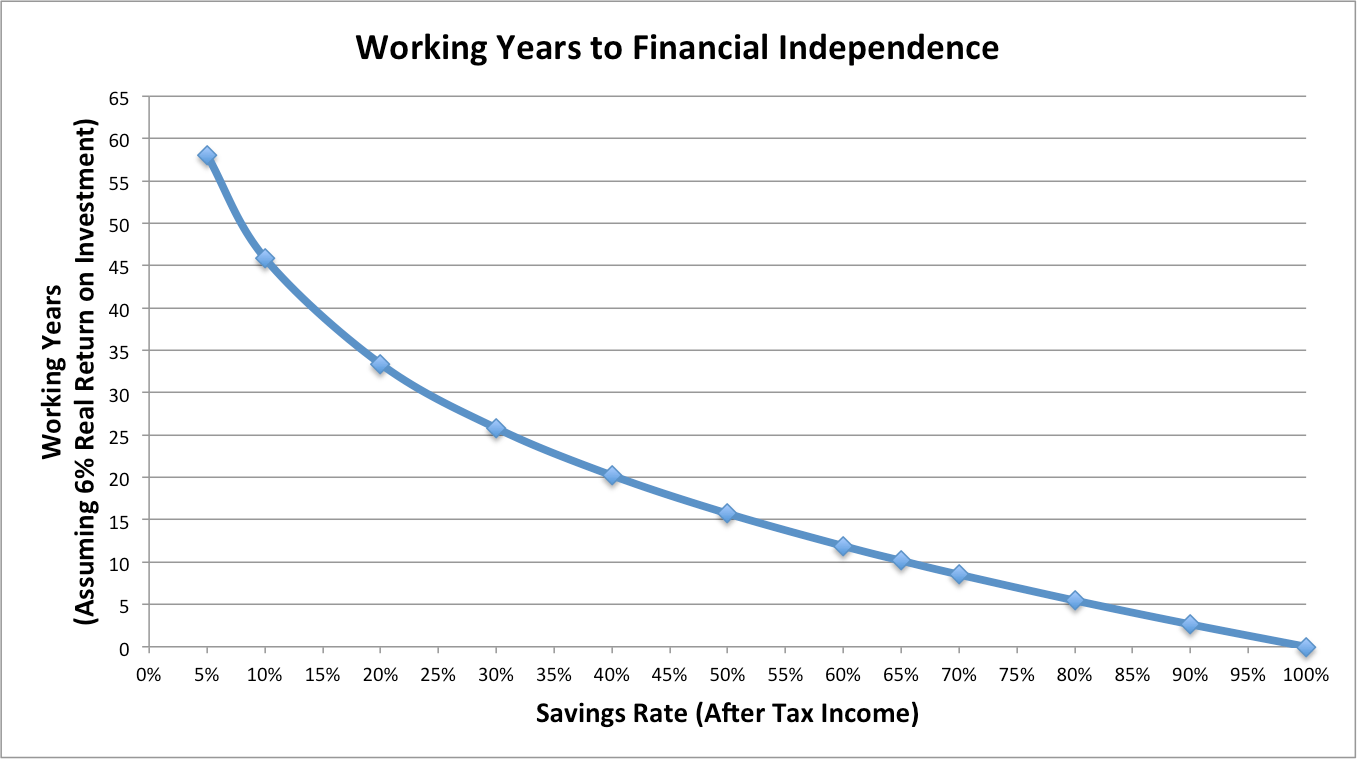

6. Lastly, I've been thinking a lot about the question from Module 1: "What is wealth?" I've begun to realize that how you feel while you're working towards financial freedom is just as important as the math. And so much of it about feeling grateful. Here's a quote from the comedian Ben Stein:

Now, I have found that I cannot predict the stock market except over very long periods. I cannot tell you when the housing bubble will burst - only that it will burst. I cannot tell you when the dollar will stop rallying - only that it will stop. So I cannot tell you anything that, in a few minutes, will tell you how to be rich. But I can tell you how to feel rich, which is far better, let me tell you firsthand, than being rich. Be grateful. - Ben Stein

I've been wanting to add more gratitude in my life. As we talked about in class, we all have an internal script that more money will make us happier, but statistically, it's not true. I was hit with that a lot on my big trip around the world this year. visiting countries where people experienced traumas and dfficulties (Vietnam, Rwanda, India, South Africa) that we Americans can't imagine. I got a strong sense that in America, we have so much more, yet are no more grateful for our lives. The leading researcher on gratitude, Robert Emmons, talks about the unhelpful attitudes we have in our country, a perception of victimhood, a sense of entitlement, and the belief that we're self-sufficient. And our culture of consumption makes us think of ourselves as producers and consumers, instead of being held in a weave of interdependence, as receivers of gifts. And we have so much.

All this thinking as got me to offer a PUGS course, in October called The Appreciation Project. It's about the science and practice of gratitude. We'll keep a simple gratitude journal and then do a one month project where we each choose 20 people in our lives who we're grateful to, and write letters of appreciation to them. If you feel called to bring more gratitude to your life (and you live in Portland), consider signing up. Would love to see some FF alumni in that course.